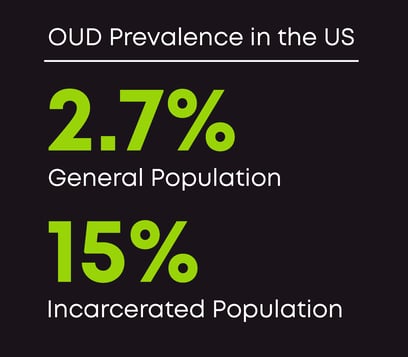

The already devastating opioid use disorder (OUD) statistics are even worse when applied to our justice system. The prevalence of OUD across the country is estimated to be somewhere between 2.04% to 2.77%. For people in custody, this figure increases five-fold: 15% of the incarcerated population has OUD.

Despite a clear need, only 1 in 8 correctional facilities offer medication to treat OUD (MOUD), according to research from the Jail and Prison Opioid Project. As an underserved community, people in custody are unable to seek and enroll in treatment on their own. I’ve always held the belief that ignoring this population in our fight against the opioid epidemic not only leaves a large population in needless suffering, but it also holds us back from any semblance of success in reducing the impacts of OUD in our country.

I’m proud to say that Bicycle Health recently surpassed the one year anniversary of our partnership with Wellpath and the Federal Bureau of Prisons (FBOP) to great success. Our work is taking hold: So far we’ve provided treatment to over 1,200 patients residing in 122 FBOP Residential Reentry Centers (RRC) across 42 states.

There’s still work to do, and policies to enact, but I believe that our model of innovative treatment through tele-MOUD will not just reduce recidivism (by as much as 25%), it will also break down current care barriers that must be overcome. Our success so far is just the beginning, but, to me, it’s a positive indication of change.

Flexible treatment modalities are essential for people in custody

Overcoming barriers to MOUD treatment access can be achieved by supporting treatment modalities that have the flexibility to fit within the confines of what correctional facilities are able to offer. We saw first hand when our program began last year.

Because resources are limited in prisons, implementing an on-premise treatment program is difficult. Instead, treatment options that don’t require the same level of operational infrastructure can be immensely impactful. Our telehealth approach to treatment, for example, allows providers from around the country to meet patients where they are—whether it’s in a jail, prison, or residential reentry center (RRC). Reentry in particular is a time when care is vital as adults are already faced with the overwhelm of a job search and reestablishing relationships. We’ve found that providing treatment to this subset immediately upon their arrival to halfway houses has significantly eased the burden of reentry for the better.

And when it comes to administering medications, there are different treatment methods that are a better fit for correctional facilities, too. Buprenorphine (the gold-standard of OUD care) is commonly offered as Suboxone, a once-daily sublingual medication that combines buprenorphine and naloxone. But the medication can also be taken as Sublocade, an extended-release injection that only needs to be administered once a month.

Within correctional facilities, where administering medications is more operationally complex, monthly injections have massive potential to increase treatment feasibility, easing the process for patients and providers. At Bicycle Health, we recognize the benefits Sublocade can offer patients and are now providing the medication to all of our patients through a joint effort with Albertsons pharmacies.

Combining telehealth and Sublocade monthly injections is a proven and effective method for increasing MOUD treatment access within correctional facilities. This approach minimizes complicated logistics and infrastructure needs and can bring treatment to even more facilities—something we look forward to achieving this year (and in the years to come).

Policy efforts are making progress, but they must align with innovation

The research coupled with our experience over that last year makes clear to me that the effectiveness of tele-MOUD is critical for people with OUD in our jails and prisons. But policy makers must acknowledge its effectiveness, as well.

We saw glimmers of hope in the last year: first, the Biden administration instituted a policy change that strives to increase MOUD access in jails and prisons. With the change, states are able to ask Medicaid to cover the cost of substance use disorder treatment, including MOUD, during the 90 days prior to an individual’s release. Though this limits treatment to shortly before reentry, treatment during this time can help soften the already challenging reintegration process and lessen the risk of a dangerous or even fatal overdose.

The Medicaid coverage expansion was a critical step, but without concrete support for long-term access to telehealth, these scarce medicaid dollars could be directed in the wrong direction (toward ineffective or out-dated treatment programs). This is why we must rally support around the TREATS Act which was reintroduced in the Senate in November 2023. The bi-partisan bill will waive regulatory restrictions on prescribing MOUD via telehealth, creating long-term access to telehealth care—a crucial component to OUD care for most, but especially for people in custody.

The solutions are obvious. We can have a profound impact in addressing the opioid epidemic by increasing funding and support for MOUD programs in correctional facilities. The benefits of treatment extend far beyond managing OUD, too. Administering MOUD prior to release is likely to reduce post-incarceration criminal behavior and recidivism. We are poised to make headway this year treating this population, but it is imperative that policy efforts align with our proven approach if we are to achieve lasting change.